‘I fought in the Second World War and I have ten medals. The fighting was non-stop. I kept fighting and fighting but I didn’t die. I fought against the Japanese. I also fought in Germany. I have been to many places to fight. I didn’t die.’ Rfn Chandra Bahadar Garbuja had walked from his home in Shikha to the secondary school I was visiting in the same village. He carried a walking stick he told me the British government had given to him, having served for the British Army. He told me he was 105 years old, though the GWT data recorded him at 92. ‘Was it difficult?’ I asked, knowing full well the answer would be yes, but I was intrigued to hear more of his wartime experience. Chandra laughed. ‘To fight in a battle is very hard. I kept on fighting. I was hungry for fifteen days. In the jungles of Burma. They used to have wild banana. We saw buffalo. My senior officer told me to kill it. I took out my pistol shot it twice and killed it. We then cut it and ate it. The British also dropped rations from parachute. The enemy stole away all the rations and we were hungry.’

‘It must have been the same for my Grandfather’ I pondered, as I thought about how my own father’s father had fought in the same jungles all those years go. ‘The best soldiers I ever met’ was his own comment on his Nepali comrades.

Chandra was just one of the many Gurkha veterans I met during my trip who might have served alongside my grandfather. He had travelled with the British Army to Burma in 1943 to fight against the Japanese and had returned home with many war stories of his own. He’d told tales of their determination, bravery and resilience. In my young mind, he’d painted a picture of a stoic warrior hailing from this majestic mountain kingdom and had instilled in me the desire to visit this wonderful nation they called home, and if I were lucky, I’d get the chance to work with them, just as my grandad had.

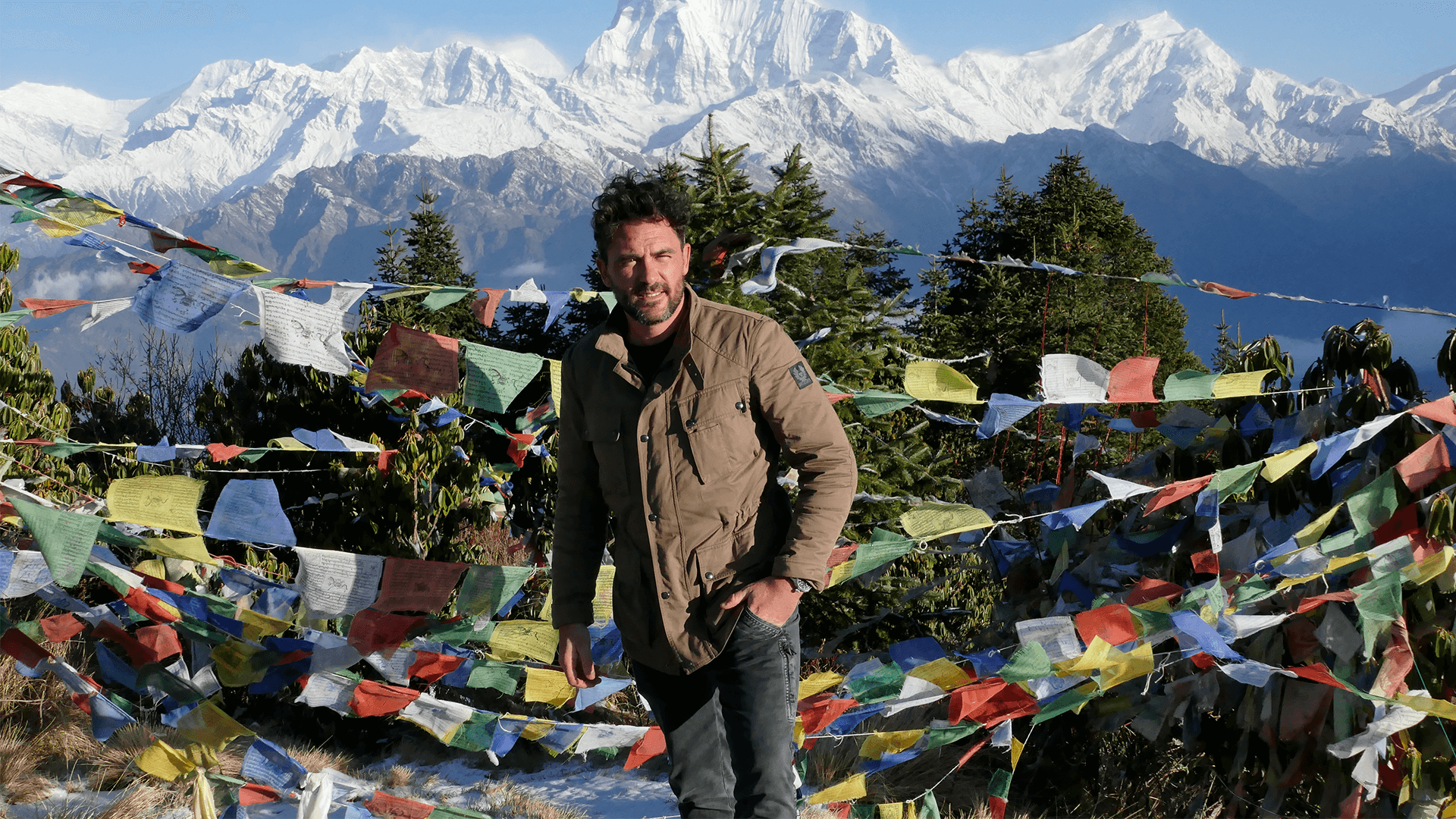

I’d first visited Nepal as a 19-year-old solo backpacker. Unfortunately, I’d arrived in a prolonged period of banda, the Nepalese word for ‘closed’, which meant the whole nation was on strike shutdown. A Nepalese boy of my own age, Binod had felt sorry for me and took me to his family home in the hills, to avoid any trouble. It was the kindest gesture I had ever experienced from a stranger, and it set the precedent for the hospitality I would receive in Nepal to come. It was with Binod I last found myself in Pokhara, where the Gurkha Welfare Trust headquarters are located and where I would be spending the next couple of days visiting the charity’s projects. We’d remained good friends since he’d rescued me that day in 2001, and when I was organising another of my journeys thirteen years later, to walk the length of the Himalayas, I couldn’t think of an individual more suitable to accompany me for its duration. The expedition had gone almost seamless until we reached Rukum District. We were only a week’s walking away from reaching Pokhara, our next big milestone and Binod’s home. But an unfortunate car accident one night left me with injuries that required surgery in the UK, so the rest of the walk was postponed until I had been sewn back together. Despite my discomfort, as soon as I was fit, I was eager to return to Nepal, to reconvene with Binod, and to continue exploring the country together; the country that had felt to me like a second home since that first day I’d visite

The Gurkha Welfare Trust were hosting me for five days. Given how much work they do, and what limited time I had, my itinerary was jam-packed, but I knew I was in the best hands to show me the extent of their hard work. The first day we visited a retirement home, provided by the Trust to Gurkha veterans, their wives and their widows. Those that had fought during the Second World War told me proudly their army numbers, before describing their service, what battles they’d fought and what injuries they’d suffered. They spoke gratefully of the provisions of the GWT, who make sure they have somewhere to sleep, food to eat and are medically checked over regularly. A school visit later that day allowed me to appreciate that the focus isn’t just on the elderly, but they are also invested in the descendants of the veterans, and their futures. Access to resources and education in rural Nepal is very limited, so I was overjoyed to witness first-hand that the charity was building another school wing and had established a water system which already supplies 60 households with fresh, drinkable water.

‘We are so happy from this project. We get clean drinking water. Before this, there was a problem of water.’ Binod Gurung, the chairman of his village’s water project beamed. ‘Before, there were some communal taps but the water was not sufficient. Some villagers even had to walk half an hour just to collect water. Now every household has their own individual tap, where water comes 24 hours. We are very happy now.’ I shook Binod Gurung’s hand and thanked him for showing me his village’s water system.

As I sat down back at my desk back in London, I flicked through the photos I’d taken of the people I’d met that week, and was transported back to the tranquillity of the Himalayas. I stopped at the picture of Binod Gurung standing proudly by his tap. He was grinning from ear to ear. As were all the men and women in the photos before him. I’m often asked why I choose to return to Nepal, when there are still so many more countries I haven’t set foot in. The answer is simple: the people. Their happiness is infectious and their hospitality incomparable. And as those sentiments lingered, I looked at my 2020 calendar and started to plan my next mountain adventure in this wonderful country.